Cocaine doesn’t kill people; culture kills people.

Actually, non-evidence-based policies, systemic racism, and ignoring indigenous wisdom kill people, but those are all influenced by culture.

True, cocaine’s not generally safe and healthy. Unlike mushrooms and MDMA (mostly illegal), it doesn’t have super low toxicity and plenty of therapeutic, mental, relational, and spiritual benefits—it’s dangerous like alcohol and opioids (mostly legal).

Yet, if you look at the percentage of users and hospital visits or deaths, it pales in comparison to legal drugs such as alcohol and tobacco. The estimated minimum lethal dose of cocaine is 1.2g, far beyond the amount most social users do on their own in a night.

It’s no surprise that Dr. Carl Hart, a neuroscientist who specializes in how humans respond to psychoactive drugs, found that most drug-use scenarios cause little or no harm and that some responsible drug-use scenarios are actually beneficial for human health and functioning.

“Not the bullshit you buy on the street that’s been stepped on. When you go to places like Columbia, and you go to the source, and you get really good cocaine… like Columbian cocaine is about seven dollars a gram and in New York, it’s anywhere between sixty and one hundred dollars a gram. So, when you go to the resource countries and get the good stuff, it could be a really good evening with you and your significant other.”

— Dr. Carl Hart

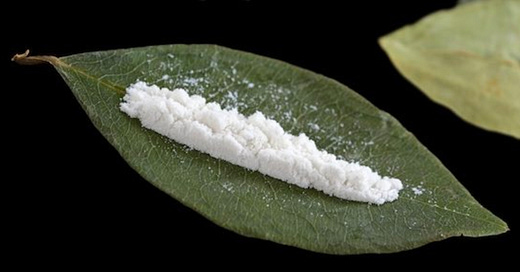

If you’ve ever seen how cocaine is made in “the resource” countries, the battery acid, gasoline, and concrete used to extract the cocaine probably has you questioning if there is such thing as “good” cocaine. Although horrible for the environment, what you’re left with, if done right, is a salt—cocaine hydrochloride.

A salt that’s much less dangerous if left inside the sacred plant. Depending on the origin of the tea bags (Bolivia versus Peru), after exhaustive extraction, an average of 4.86–5.11 mg of cocaine was found per tea bag. An investigation conducted in Bolivia found that after chewing 30 g of coca leaves, whole blood cocaine levels reach around 98 ng. In contrast, there is a large difference in what an average cocaine user is exposed to in modern times. A “line” of cocaine bought on the street contains an estimated 20–50 mg of cocaine hydrochloride.

Plus, Coca leaves include calories, carbohydrates, minerals, and vitamins. It combats stomach pain, intestinal spasms, nausea, indigestion, constipation, diarrhea, and altitude sickness. Really, the only thing it has in common with the white powder is that people use it to energize and socialize.

Coca-leaf usage is deeply ingrained in the daily life of the Cusco and Sacred Valley region, comparable to the widespread practice of consuming mate in Argentina. It's a ubiquitous activity, with people from all walks of life partaking in it regularly. Much like how a Cusqueño is often seen with a wad of coca leaves, an Argentine enjoying mate from a gourd is emblematic of their respective cultures. However, in Peru, the significance of coca consumption extends beyond mere habit; it is intertwined with profound religious traditions.

In Peru, the coca leaf is regarded as having a value akin to gold. The Incas esteemed coca for its medicinal attributes and its central role in their sacred ceremonies and traditions. Traces of the leaves have been found in mummies dating back to around 1,000 B.C., showing the deep roots of these traditions.

Yet, the salt’s out of the leaf and is here to stay. Especially when the salt has been used to fund violent right-wing movements the CIA lets slide, saves banks, and keeps white people at the top of society and madness—especially in the United States, the biggest cocaine consumer of all, followed by the UK and Australia.

In the USA, cocaine has become heavily racialized and politicized, especially since the more affordable and smokable version, crack, came into play. The media depiction drove U.S. drug policy and shaped both political debate and public attitude towards crack cocaine. The U.S. government's response at this time focused on managing the perceived crack cocaine epidemic by criminalizing rather than providing treatment facilities or healthcare services for people who use crack cocaine.

The portrayal of crack cocaine in the political sphere intensified in 1986 following the highly publicized death of Len Bias, a young African American basketball star whose demise was widely attributed to an overdose. Bias inadvertently became a prominent figure representing the perceived hazards of crack cocaine due to extensive media coverage surrounding his passing. His death and the subsequent media attention served as catalysts for substantial shifts in drug policy, notably culminating in the enactment of the U.S. Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. This legislation introduced mandatory minimum sentences for individuals convicted of possessing crack cocaine.

The result? 100:1 sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine offences was enforced despite the scientific community demonstrating that both powder and crack forms of cocaine produce identical and predictable physiological effects, negating any need for a difference in minimum sentencing.

Cultural perceptions regarding individuals who use crack cocaine have contributed to the perpetuation of American policies that disproportionately target specific racial populations, particularly black communities. Data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration indicates that there are no statistically significant variations in the rates of illicit drug use among different racial and ethnic groups. However, statistics from the U.S. justice system for the fiscal year 2019 reveal a striking disparity, with 81.1% of individuals convicted of trafficking smokable cocaine being black.

In the United States, discussions surrounding crack cocaine have predominantly centred on issues of race, whereas in France, the discourse has been more a matter of social and urban disparity. However, it’s a bit harder to investigate race because racial designations based on self-identification are not available in France. Additional qualitative ethnographic research illustrates a connection between individuals who use crack cocaine and migrants, revealing another dimension that underscores racial and ethnic disparities within postcolonial France.

The challenges in explicitly addressing racial inequities can be partly attributed to the lens of "French Republic Universalism," which asserts that all French citizens, regardless of their origins, should be regarded as equal members of the nation with the same rights. This a beautiful sentiment, but some argue this framing brings about a colour-blind political discourse that is unable to publicly recognize discrimination against people of colour according to the French colonialist ideology.

However colour-blind the discourse may be, there’s no denying France is systematically more equipped to serve the healthcare needs of people who problematically use crack cocaine compared to the U.S.

Starting from the late 1970s, alongside a stringent drug policy, France has instituted a robust, publicly funded drug treatment system that includes harm reduction services, aiming to better cater to the health requirements of individuals involved in drug use.

Whereas individuals who use crack are often associated with the lower class, cocaine has become classless. The media has succeeded at reframing crack as a poor consumer choice, but cocaine’s still going strong. In 2019, a Home Office drug review found that 42% of users were in managerial roles, 35% were manual workers, and 3% were unemployed.

Although these numbers are based in London, it wouldn’t be surprising if they apply to the rest of the country and other Western nations.

Connor reminds me of a friend who walked away from a drilling job that paid about £80,000 a year rather than submit to a drug test (a salary of £80,000 puts this person in a middle-class wage bracket, but rigs are still working-class spaces and he remains working class). Every company has its own rules, but failure usually means instant dismissal. Workers are given the option of resigning before they take the test. Many pretend they’ve had an urgent call from home, which buys them a few extra days onshore, where they can wait for the drugs to leave their systems. Connor says senior management rarely has to take these tests. Companies can’t risk losing key personnel and don’t want to deal with the fallout. The higher up the food chain you go, the greater the potential for scandal.

Tabitha Lasley

I could write a similar paragraph for those working up north in Canada's oil industry. To an extent, our work culture dictates the drugs we do. If your job requires drug tests, cocaine is a “safer” option than marijuana because it leaves your system fifteen times as fast. It’s also common for the douchebags in finance (a way to hate themselves a little less) and anyone who works in the restaurant or nightlife industry, where a quick “pick me up” is easier to handle and hide than longer-lasting effects of methamphetamine (more popular among those who work their asses off solo—like truck drivers).

Then there are artists of academics. We have the time to spend 4-12 hours tripping out on mushrooms, LSD, mescaline, or whatever else we find fun enough to write about or, if we’re seasoned enough, on.

Obviously, these are stereotypes. The truth is anyone can do any drug they want. As Dr. Carl Hart argues, adults should be free to choose how they alter their consciousness. Most drug policies are based on assumptions and anecdotes, but they are rarely based on scientific evidence. We need to decriminalize drug use through policies that are scientifically based rather than heavily influenced by social determinants such as race and class. But most of all, we need to stop stigmatizing drug use. It’s the stigma more than the drugs that cause discrimination, addiction, behavioural health problems, and negative social norms. We are all one consciousness, and how we choose to experience it subjectively is not to be judged but studied and explored.

If you believe my work has value and enjoy reading on a platform that doesn’t steal your attention with ads, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and sharing my work with your family and friends.

I need to think

Meanwhile-I just now learned that this book's been translated but didn't have an opportunity to check whether translated well. It's an amazing book. I remember beeing very stricken by it. I recommend it https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Novel_with_Cocaine