Time is a construct

— Albert Einstein, Lau Tzu, Eckhart Tolle, Aleksandar Hemon, and the millions of people who have meditated, fallen deeply in love, and tripped balls.

I won’t let societal constructs define my time.

Love, drugs, meditation, and other spiritual experiences influence our perception. One can explain how the various hormones and neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, melatonin, and oxytocin, affect our subjective understanding of time, but what I’m most interested in is culture.

Since culture is inseparable from language, what we speak inevitably affects how we think about time.

Boroditsky and colleagues found significant differences in time representation between English speakers who perceive time as going from left to right and Australian Indigenous peoples who perceive time as going from east to west. The same study also investigated people's responses to rescheduling a meeting. The question of how we see time moving through us or us moving through time is influenced by linguistic factors, with some thinking more in a time-moving perspective while others adopt an ego-moving perspective.

However, English speakers are split down the middle. If I ask you, "Wednesday's noon meeting has been moved forward by two hours. What time do you think it is?"

Some say 10 AM, and some say 2 PM. 10 AM equals the time-moving perspective, and 2 PM means the ego-moving perspective. In other words, do you see time moving through you, or are you moving through time?

People also switch their perspectives depending on the event. If we're looking forward to something, we might use the ego-moving perspective, but if we are dreading something, it might be the time-moving perspective.

People who think differently about space are also likely to think differently about time. For example, Boroditsky and her colleague Alice Gaby gave Kuuk Thaayorre speakers sets of pictures that showed temporal progressions—a man aging, a crocodile growing, a banana being eaten, and so on. They then asked them to arrange the shuffled photographs on the ground to indicate the correct temporal order.

They tested each person twice, and each time they faced different cardinal directions. English speakers given this task arranged the cards so that time proceeded from left to right, whereas Hebrew speakers tended to lay out the cards from right to left. This shows that writing direction in a language influences how we organize time.

The Kuuk Thaayorre, however, rarely arranged the cards from left to right or right to left. They placed them from east to west. That is when they were seated facing south, the cards went left to right. When they faced north, the cards went from right to left. When they met east, the cards came toward the body, and so on. The crazy thing is that the experimenters never told anyone which direction they were facing—the Kuuk Thaayorre already knew and spontaneously used this spatial orientation to construct their representations of time.

Boroditsky also investigated the differences in the conceptions of time between Mandarin and English speakers. The study found that Mandarin speakers think about time vertically, associating earlier events with being "up" and later events with being "down." In contrast, English speakers conceptualize time horizontally, associating events in the past as being "behind" them and those in the future as being "ahead."

Of course, language is only a part of how culture affects our perception of time.

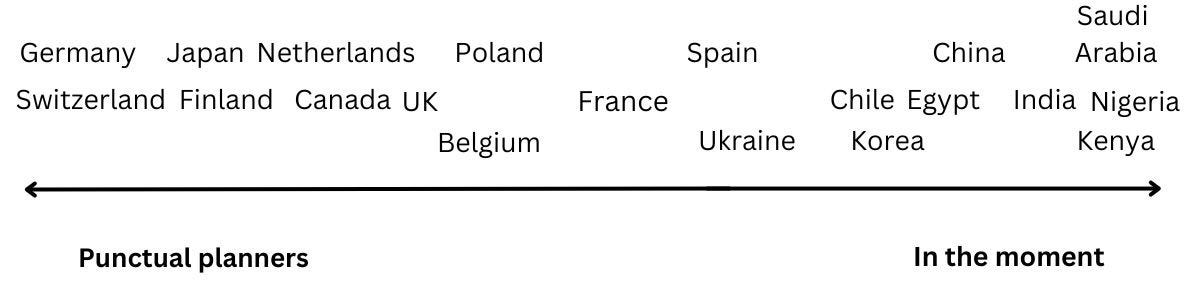

What is considered on time in Spain is not what it considered on time in Canada, and definitely not in Germany. Sure, Spanish people take two hours to explain something an Englishman would wrap up in five minutes, but that’s not the language per se. Factors like economic instability, higher degrees of collectivism, and how delicious the food is (the more delicious, the less punctual) impact how punctual or time-flexible a culture is.

Okay, the food theory is my own and strictly based on correlation, but just take a moment to think about the traditional foods from Germany, The Netherlands, Scotland, Norway, Russia, and Canada compared to Italy, Spain, India, Senegal, and—I’ll finish here before you stop reading to eat.

Plus, I’ve become more interested in researching what unites rather than divides us. Understanding how cultures shape our differences is a great way to overcome individual or team disputes when dealing with multicultural environments. That why my English classes mix in cultural competence training.

However, I’ve become more interested in what unites us rather than divides us. And what unites our shared humanity more than anything is what we’re losing—a sense of the mystical.

Throughout my life, I thought I enjoyed being right. My fascination with rhetoric combined with solid memory and an ability to provoke people won arguments, but never added any true value to my life.

Can I prove I met someone in a past life? Can I prove that time doesn’t exist with them? Of course not. I can’t because love is an endless mystery that explanations can’t do justice. Yet, I can explore it.

My next article examines the possibility of past lives—something I didn’t believe in until a series of shared dreams, déjà vu, and inexplicable attraction.

If you believe my work has value and enjoy reading on a platform that doesn’t steal your attention with ads, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and sharing my work with your family and friends.

This may be my favorite of your posts. I want to sit with what you have shared. I may return with more reflections but just wanted to drop into comments and say this for now.

What bout I speak Cantonese from the start then mixed with English, and then I learn to read and write in English. How do I think about time? I believe I perceive time like the English "speakers", in my case, the "readers". I think it'll be interesting if there is a study that also test spoken vs written language that a person posses.

As for your food theory correlation with on time, I have my own theory. The warmer a place is, and the lesser the seasonal changes are, the less on time the culture would be. :)